[photo of vat here]

The LPRU is able to study the artefacts of the Lye Planet because they were stored by their creators in specially built vats filled with a preservative fluid. This novel technology was used throughout the world, and seems to have emerged quite suddenly at the beginning of the Decline for the specific use of artefact preservation (there is no evidence that the vats were widespread before these environmental changes, or had any other application, such as food preservation). The existence of the vats is a riddle that continues to perplex LPRU researchers: for why is it that communities with no conception of history and a non-linear attitude to time decided that the past was now something to preserve? And furthermore, for whom were they preserving these objects (keeping in mind that the imminent extinction of the planet was widely acknowledged, and that there is no writings which reference an afterlife or the possibility of inhabited alien worlds)?

The concept of ‘future’ first emerges in the Lye artefacts as the recognition that the old cycles are disappearing and that new things will come to pass that have not occurred before. In other words, ‘future’ is a by-word for uncertainty and anxiety. Prof S A Leach has noted how the author of LPA186.480.26 speaks fearfully of the increasing waves of migration that came in the early period of the Decline:

‘Push Here from you, We told Them when Now was a Seed — put on again your Fabrics of another Place, You are overflowing You are too much Movement’

Leach observes that these nomads’ reputation for storytelling gave their perceived dangerousness a double meaning:

‘As more and more people passed through the settlement, even in light of the need many must have been in, the community’s insistence that these were “story-tellers”, out for diversion and nothing else, became all the more trenchant […] As a term of abuse or indictment, it designated the migrants as simultaneously bearers of fictions, and, in a sense, fictions themselves — in that they represented departures from the actual, the knowable […] [These] migrants were visible reminders of everyone’s vulnerability to the effects of the Decline, of everyone’s possible future displacement, and, ultimately, of the community’s eventual fate: to take on the status of fiction (non-existence).’

This anxiety is a direct consequence of the emergence of a future without past. In light of this, many have interpreted the vats as an attempt to preserve the present moment (to re-imagine it, even) rather than to leave behind a historical record; the preservation was a day-to-day practice to help mentally forestall hurtling into the unknown. Kiran Leonard somewhat disagrees in his analysis of LPA210.045.42 (the Husband folio); speaking of ‘a darkness which cannot even be described as the future’, he claims that, at least in the case of that folio’s author, the crisis led not to a rapid and nervous realisation of linear time but to a theorisation of a ‘second instant’, the strenuous hope that at the culmination of the Decline time itself would reconfigure, as if the whole universe was itself a stem on a larger, unknown landscape.

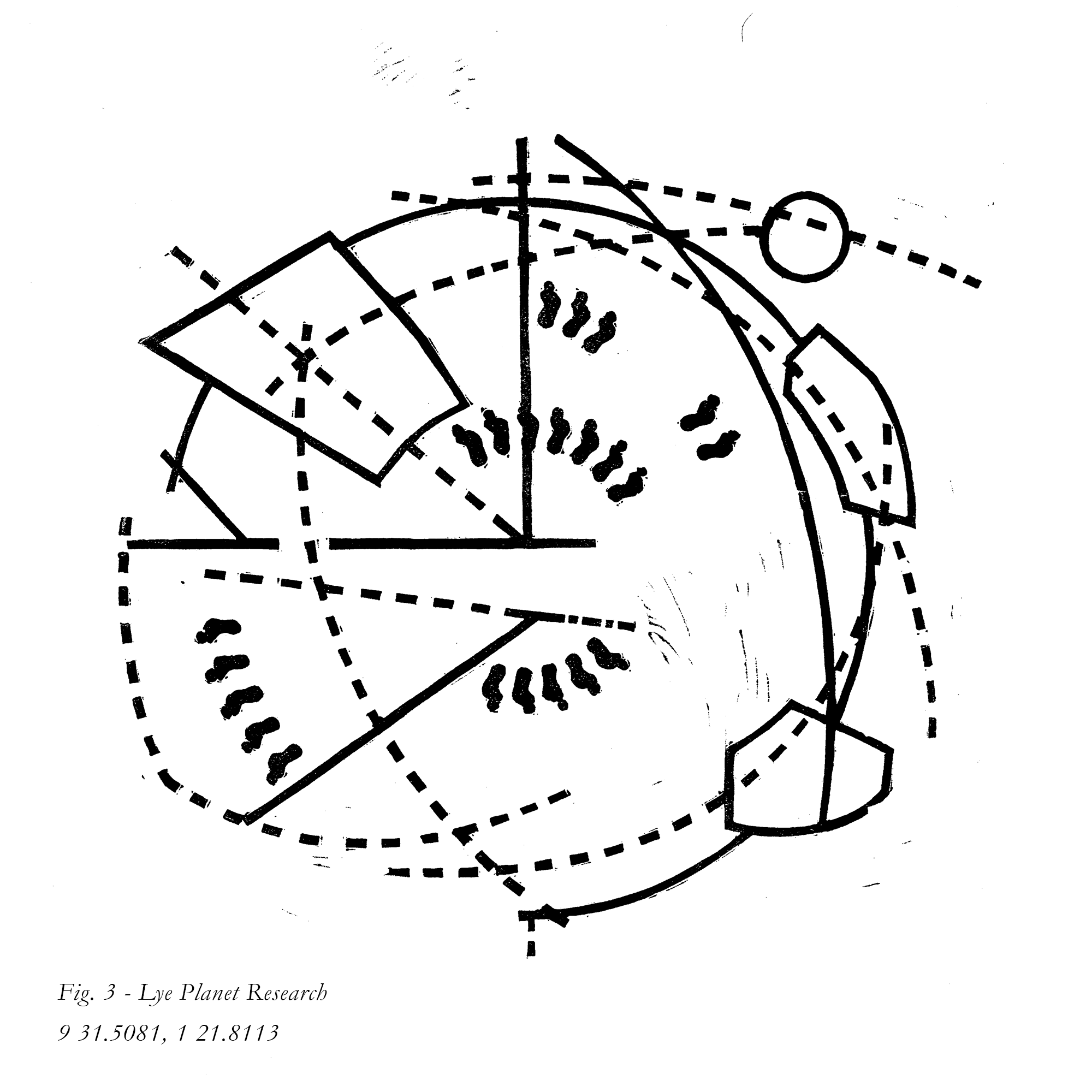

Others still have theorised whether the production of artefacts was an attempt to effect planetary transmigration through text, words after all being their own entities and likely to exist after the extinction of the world organism and its stems. This is not certain; for one, there does not seem to have been much of a consensus on what would happen to the planet after its inhabitants were deceased (another reason why many are skeptical of the vats as being intentional markers of history). However, in the Moorland diary, the Husband folio and many other Decline-era artefacts, there seems to have been the realisation that the artefacts could allow for the transformation of the world into text and image, and another kind of perpetuity. At its most extreme, some have argued that LPA071.582.71 (the Monan Grave Diagrams) could be interpreted in this way: not plans for mass burial or even historical documents, but as literally enacting the transformation of the depicted inhabitants.